James Cooper’s Civil Rights Artifacts spotlights South Jersey

BY CLYDE HUGHES, AC JosepH Media

GALLOWAY – For anyone doing civil rights work in the 1960s, Mississippi was hostile territory with little chance for meaningful redress – and Atlantic City attorney James Cooper knew it.

In a letter to his law partner, though, Cooper said he did not realize just how bad things were there for African-Americans in their effort to obtain basic civil rights. Yet, there Cooper was as part of President John F. Kennedy’s Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights defending blacks in a trial as a volunteer.

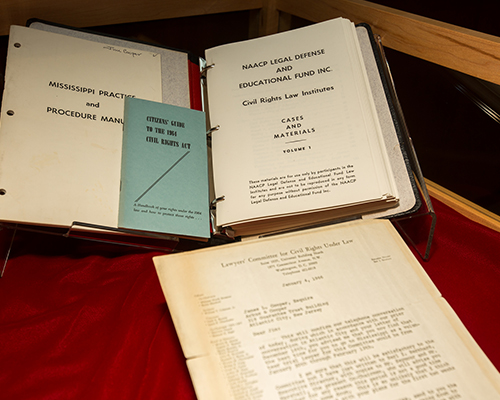

Cooper – a founding partner of Cooper Levenson, Attorneys at Law – died last year but a briefcase with documents, maps, and trial notes from his trip will allow part of his legacy to live on at Stockton University. His daughter Cynthia Cooper donated the briefcase and documents from the 1966 trip to the university earlier this month in a special event accepting the information for its archives.

“He mentioned in his notes that he was worried about being followed, maybe even by police,” Robert Gregg, dean of the School of General Studies, said a presentation of the artifacts Aug. 6 before the invitation-only presentation.

“This was two years after Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner in Mississippi, so they knew all about the dangers. It was three years after the death of Medgar Evers. This was clearly not a great time to be down there,” Gregg continued.

The deaths of James Chaney, a 21-year-old African-American, Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, who were both white, proved to be one of the turning points in the Civil Rights movement. The case was fictionalized in the popular Hollywood movie “Mississippi Burning.”

Against that backdrop of domestic terrorism, Cooper spent two weeks in Mississippi representing African-Americans who could not find local lawyers to defend them. The donated briefcase contained maps, trial notes, newspaper articles and photographs from that period.

“For me, the letter to his law partner (about his time in Mississippi) was amazing,” Heather Perez, Stockton’s archivist, told Front Runner New Jersey. “He talked about how the grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan sat in the front row of his trial not saying a word but starred the whole time at the jury. Obviously, (Cooper) was worried about his own safety, but also justice or the lack there of.”

Perez said that according to Cooper’s notes, the Jim Crow-era separate doors, water fountains, and the like for whites and African-Americans were jarring to him.

“He talked about going to see a doctor and was startled to see different entrances for African-Americans and whites,” Perez said. “He took pictures. It was something he never thought about on a personal level until he went down there. The two doors were very concrete for him.”

Gregg said during the trial he was involved in, Cooper helped represent three civil rights workers who faced disorderly conducted charges in a fight, along with three Ku Klux Klan members. The Klan members demanded a jury trial and in the end in front of an all-white jury, the civil rights workers were all found guilty and the Klan members innocent.

“They were all fighting each other, but the whites were found not guilty,” Gregg said. “In one letter he explained he wondered if things were as bad as the media was making it out to be and learned it was many times worse.

“A white person could shoot a black man with impunity and no jury, no white person, would stand to help to convict that white person. For him, it was quite powerful,” Gregg added.

Gail Rosenthal, director of the Sara and Sam Schoffer Holocaust Resource Center at Stockton said she hopes the artifacts left behind by Cooper will help students make the connection from the 1960s to today. She said she remembered Cynthia Cooper talking about how her mother cried when James Cooper left for Mississippi because she feared that me may not return safely.

“We’re hoping this will make the story come alive,” Rosenthal said. “They will be able to read some of the documents. We’re sharing it with our faculty. We hope they will be the people who will be the messengers so 10 years from now, I may not be teaching, but I’m hoping that a student will stop and say, ‘How is Jim Cooper’s daughter, Cynthia?

“(James Cooper and fellow volunteer attorneys) didn’t have a strong network of people. They were isolated. Felt like they were on an island. This is the last of the generation to pass this along to the next generation. That’s why I feel so strongly about it,” she continued.

During the evening program, Cynthia Cooper, Russell Lichtenstein from Cooper Levenson, Attorneys at Law, and Kaleem Shabazz, Atlantic City NAACP president and member of city council addressed the crowd.

“James’ experience in Mississippi left an indelible mark,” Lichtenstein said, according to a statement provided by Stockton. “He was a passionate lawyer and teacher.”

Shabazz said at the program that when he was a college student he was involved with a group called Direct Action Youth. The group decided to hold a block party but failed to get a permit. But after they were arrested, Cooper appeared to represent them.

“He said it was a civil rights issue, and he won,” Shabazz said about the event. “He was a giant in Atlantic City and he had a strong, sincere commitment to civil rights and social justice. He was always involved in social justice issues.”

Shabazz told the audience, according to the Stockton release, that Cooper convincing him over multiple objections to make a day trip to Mississippi for an event in memory of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

“I said no, I do not want to go to Mississippi,” Shabazz told the audience “But, that was the kind of courage, commitment and concern he had, to go to Mississippi for an afternoon.”

Cynthia Cooper said that remembered her father talking to students about how democracy was on a slippery slope and how they needed to vote and get involved.

“The four lessons of Jimmy were: Brush the mind, broaden the base, break the mold and always give back,” Cooper said.

During the morning session, Gregg said that he could see similar parallels to the issues facing African-Americans in the 1960s and issues that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement today.

“Hopefully (James Cooper’s artifacts) will be one more step to a greater understanding to the whole movement,” Gregg told Front Runner New Jersey. “It wasn’t just about Martin Luther King. Unfortunately today, that’s where the discussion tends to begin and end. You don’t understand the kind of work people like John Lewis was doing.

“He don’t necessarily make that different down there in Mississippi at that time, but when he came back, he went to synagogues to talk about his experience and had articles written about him. He told people what it was like going on down there, and in turn that had a big impact on people.”

Rosenthal said Cooper’s work was an example of how one man can make a difference and she hopes his story and the artifacts will awake that kind of activism and critical thinking among students today.

Photo of James Cooper artifacts courtesy of Stockton University

Second Photo: Speakers at the event in memory of James Cooper — Lori Vermeulen (Stockton Provost), Leo Schoffer (Stockton trustee), Kaleem Shabazz, Cynthia Cooper, Russell Lichtenstein, Robert Gregg and Harvey Kesselman (Stockton President). Courtesy of Stockton University