1964 DNC Atlantic City Convention Remembered: ‘America Missed a Golden Opportunity’

Moderator Dr. Christopher Fisher (far right on panel) speaks to Dr. Roy DeBerry (L-R), Dr. Tiyi Morris and David Dennis, Sr. at the Mississippi to Atlantic City: Freedom Summer's Mark on America, event at Stockton University Atlantic City on Tuesday, August 20, 2024.

BY CLYDE HUGHES | AC JosepH Media

ATLANTIC CITY — For David Dennis, a chance for the United States to stand up against racism in politics did not come with the election of Barack Obama in 2008, or with the chance to elect Kamala Harris in November, but 1964 in Atlantic City.

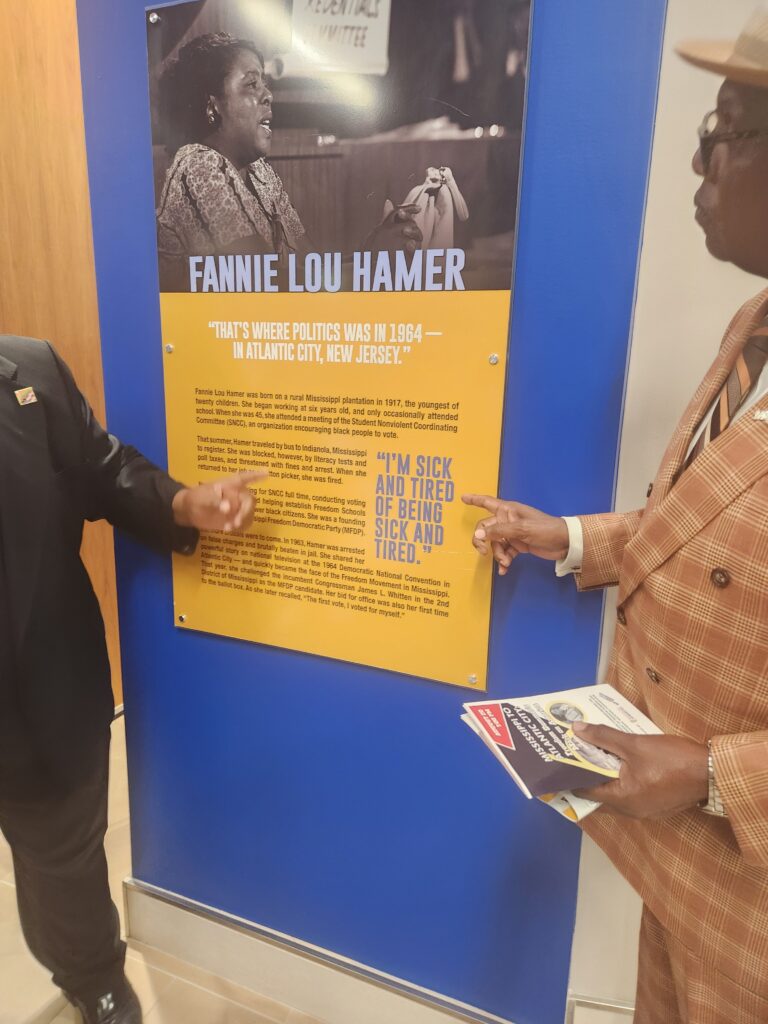

What is now referred to as Freedom Summer reached an apex during the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City with the racially mixed Mississippi Freedom Democrats, led by iconic civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, who were refused seats at the convention in favor of an all-white delegation.

Some of those delegates spoke at Stockton University in Atlantic City on Tuesday, Aug. 20 during the 60th anniversary of that tumultuous political convention, to share what happened then and the parallels they see in today’s political climate.

“America missed a golden opportunity,” David Dennis Sr., a member of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, said to a crowd in the Fannie Lou Hamer Room at Stockton’s Atlantic City campus. “The people of Mississippi, inside and outside [of Boardwalk Hall], believed in this country.

“They followed the rules and these college students who came, they honestly believed in the process. They believed if you put this out in front of the American people, that they would turn their backs on this government and say, ‘no.'”

While the Mississippi Freedom Democrats were not seated, America did get to see what happened and sped up the wheels of the Civil Rights Movement and other protests around the country in the 1960s that continues to shape the nation.

Dennis, an educator; Dr. Roy DeBerry, a retired vice president at Jackson State University; and Dr. Tiyi Morris, the daughter of Euvester Simpson, spoke at the event Mississippi to Atlantic City: Freedom Summer’s Mark on America. Dennis, DeBerry and Simpson were all members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Dr. Christopher T. Fisher, associate professor of history of The College of New Jersey, moderated the event.

DeBerry said it was initially disheartening for the Mississippi Freedom delegates to not be seated.

“There were a lot of people who were disillusioned,” DeBerry said of the feeling of many in the group after leaving Atlantic City. “They believed that the system was in place, inside the system where Fair Play could happen. Even though they did everything right, the system wasn’t allowing them to speak.”

Morris, a professor at Ohio State University who spoke on behalf of her mother, said she was probably naïve looking back on it, given the entrenched racial tensions in Mississippi. She had hoped they would be seated, but the delegates were all committed to making a difference.

The delegates talked about the dangerous atmosphere for civil rights workers in Mississippi and throughout the South. The Democratic Convention came three weeks after FBI agents found the bodies of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who were murdered while trying to get Blacks registered to vote in Mississippi. They had been missing for more than a month that summer.

“The violence was always there,” DeBerry said. “[The convention] happened the same month after the workers were found. The violence [against us] has been there since the start of this country. I think sometimes the feat was there. But the courage was there. Sometimes a little bit of craziness was there.

“That was part of Jim Crow. You don’t want to drink at the wrong water fountain, or you can lose your life. If you don’t get off the street, you can lose your life.”

City council vice president Kaleem Shabazz, who is also president of the Atlantic City NAACP, said while some may know basic facts about the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, they did not know the historical marker it carries in civil rights history. Shabazz was a young student who enjoined civil rights demonstrators just outside Boardwalk Hall in 1964.

Carin Berkowitz, president of New Jersey Humanities, which co-sponsored the program, she hoped it was educational for those who knew the history and those who came across it for the first time.

“We felt putting this on was really essential,” Berkowitz told Front Runner New Jersey. “Even though we are about something that happened 60 years ago, it’s still timely and urgent today. We’re still seeing that struggle for civil rights and voting rights in America today. We also feel New Jerseyans don’t know the stories they need to know.

“Bringing this story was a moment of power for someone like Fannie Lou Hamer. We want to make sure that the citizens of Atlantic City and New Jersey know this story. This is just a critical part of our work.”

Larry Muhammad said he was a 10-year-old boy working on the Boardwalk trying to shine shoes to make money during the convention, not knowing the history that was being made inside Boardwalk Hall.

“I didn’t know what was going on but it wasn’t until much later when I saw all of this,” Muhammad said. “This program was excellent shining a spotlight on the convention. It’s needed even more now in 2024.

“What was discussed here is needed right here. We have to tell our narrative about what happened and how it played out. Knowing this history is how we will be able to move forward to where this country needs to be at. We’re in some dark places right now and if we want to turn it around, this was a good starting place.”

Chandler Griffin and Allison Fast of Blue Magnolia Films traveled to Atlantic City for the unveiling of a memorial to Hamer that took place the morning of Aug. 20 at Boardwalk Hall. Also in attendance was Mississippi’s Republican Gov. Tate Reeves.

Griffin and Fast started documenting “freedom homes,” residences and spaces that were secretly known as safe spaces for civil rights workers visiting and volunteering in Mississippi.

“It’s really cool to come here to New Jersey and hear about Fannie Lou Hamer,” Griffin said. “We go on the Atlantic City Boardwalk and there is this memorial to Fannie Lou Hamer. It’s inspiring! It’s good for us to go back to Mississippi to tell people what we saw and share our experience. We’re glad to tell them how important it is for a place like New Jersey to embrace her at this time.”

The event was also sponsored by Visit Mississippi, the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority and New Jersey’s Martin Luther King Jr. Commission.

Follow Us Today On:

Note from AC JosepH Media: If you like this story and others posted on Front Runner New Jersey.com, lend us a hand so we can keep producing articles like these for New Jersey and the world to see. Click on SUPPORT FRNJ and make a contribution that will go directly in making more stories like this available. Thank you for reading!